The role of psychiatric comorbidities in migraine

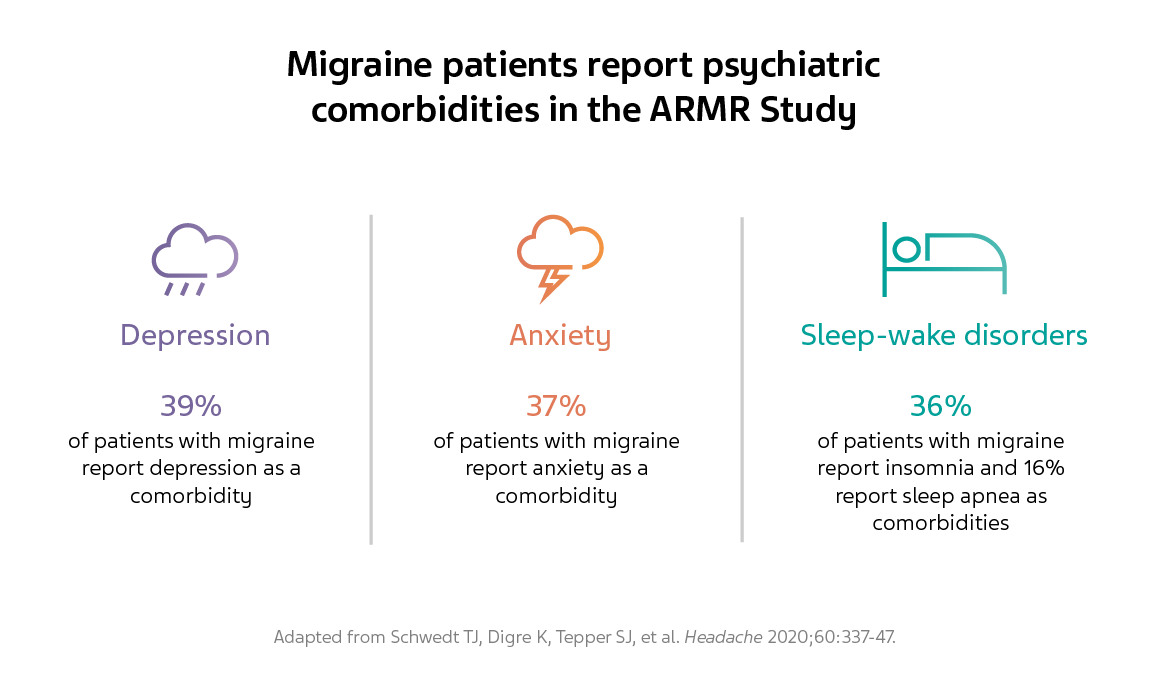

Migraine is a prevalent condition and often coexists with various comorbidities.1 This relationship is more often seen in those with chronic migraine (CM) and migraine with aura than those with episodic migraine (EM) and migraine without aura.1 A prospective, longitudinal study utilized the American Registry for Migraine Research (ARMR) to determine the most common comorbidities reported by patients with migraine (Figure 1).2

From February 2016 to May 2019, the ARMR study identified depression, anxiety, and emotional/verbal abuse as psychiatric conditions that were most frequently reported by participants.2 Similarly, the Migraine in American Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study also highlighted depression, anxiety, and insomnia as being more likely to be reported in people living with migraine.3 These psychiatric comorbidities were found to be associated with increasing headache pain intensity.3 Additionally, as the number of migraine headache days (MHDs) increased, the risk of depression, anxiety, and insomnia increased as well.3 Based on the studies mentioned, it is apparent that psychiatric conditions as a whole have a close relationship with many aspects of migraine—however, it is worth delving into specific conditions to further understand their impact in individuals.

Figure 1. Migraine patients report psychiatric comorbidities in the ARMR study.

Depression

In the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, migraine and depressive disorders were two of the three most disabling conditions worldwide in terms of years lived with disability.4 It is well known that depression and migraine have a bidirectional relationship;5 the question then becomes to what extent does one condition affect the other? A twin study attempted to answer this question and found the genetic correlation between the two conditions to be significant.6 However, the environmental correlation was non-significant, implying that the relationship may not be causal but rather be rooted in a shared etiology.6

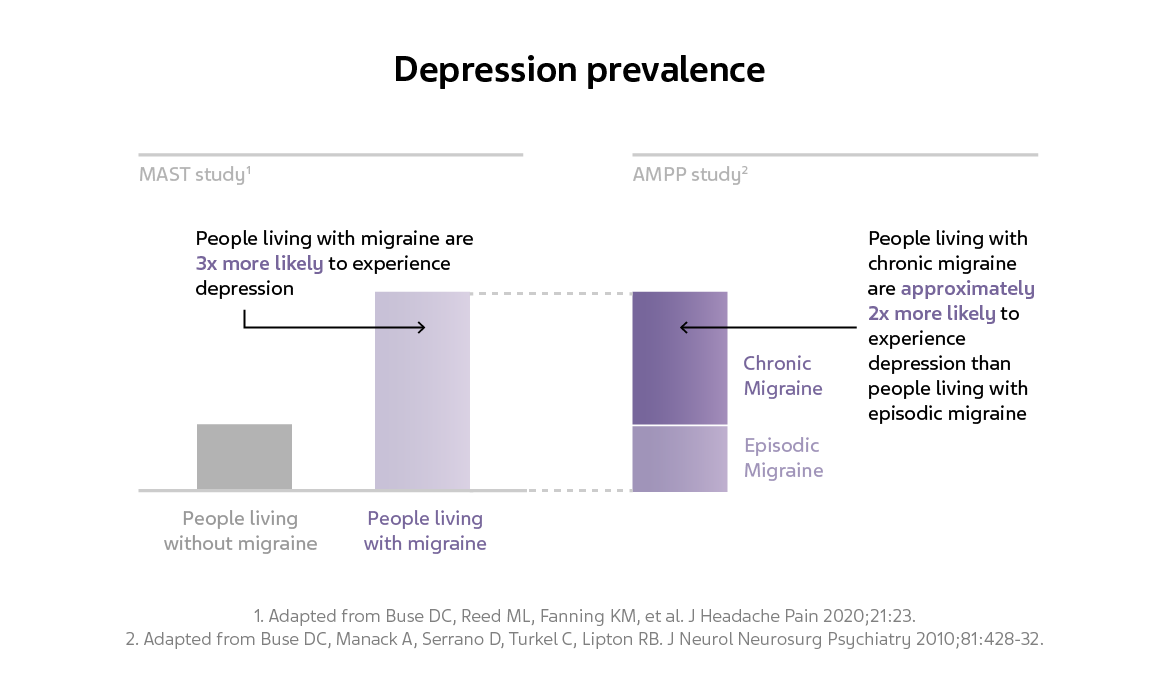

Clinically, the ARMR study noted that approximately 39% of patients with migraine reported depression as a comorbidity.2 Comparably, the MAST study found that people living with migraine were three times more likely to experience depression in comparison to their counterparts without migraine (Figure 2).3 The odds of depression were lower in individuals with migraine who were older, married, employed, and had an increasing income.3 Alternatively, the odds were higher in those who were white, had an increased number of MHDs, and experienced moderate to severe headache pain.3

Unlike the ARMR and MAST studies, the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study focused on the variation in comorbidities between people living with CM and EM.7 Results indicated that those with CM were approximately twice as likely to have depression in comparison to those with EM as measured by (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) PHQ-9 scores (Figure 2).7 Identifying people at risk for both migraine and depression is important, as progression from EM to CM has links to depression.8 Using longitudinal modeling to predict factors that may contribute to new-onset CM in people with EM, the AMPP study demonstrated that overall depression remained a significant predictor.9 Upon exploring the dose-response effect of depression, it was found that the risk of new-onset CM increased with the severity of depression.9

Figure 2. Depression prevalence in the MAST and AMPP studies.

Anxiety disorder

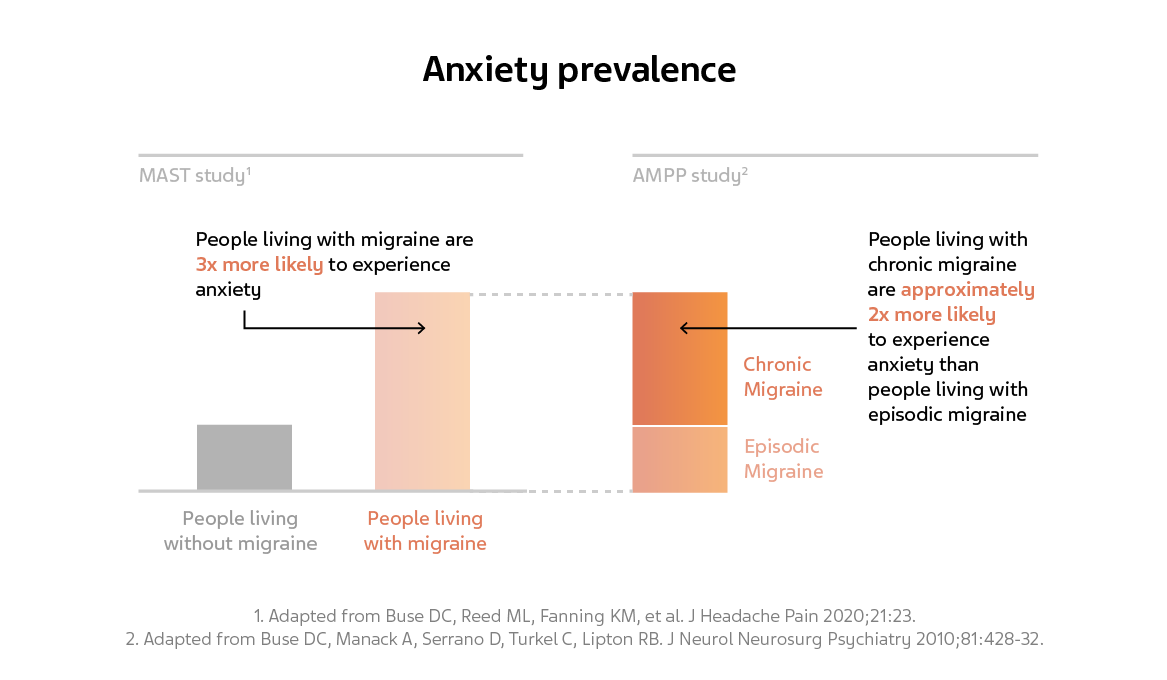

Similar to the percentage of depression reported by the ARMR study, 37% of patients with migraine reported anxiety as a comorbitiy.2 The MAST study found comparable results as people living with migraine were three times more likely to experience anxiety in comparison to their counterparts without migraine.3 Akin to depression, the odds of anxiety in the MAST study were found to be higher in younger individuals with migraine than in older individuals.3 Furthermore, being male, married, employed, and having an increasing income was found to be associated with a lower risk of anxiety.3 However, this risk increased with being white, having an increased number of MHDs, and having moderate to severe headache pain.3 When further classified by type of migraine in the AMPP study, people living with CM were approximately twice as likely to report anxiety as a comorbidity compared with those living with EM (Figure 3).7 Identifying individuals at risk for both anxiety and migraine is only one part of treating people living with migraine; an exploratory study observed that addressing anxiety sensitivity led to better headache outcomes.10 This is in line with other prospective studies that state that better headache control can be achieved by treating anxiety.11

Figure 3. Anxiety prevalence in the MAST and AMPP studies.

Suicide ideation

Suicide is frequently associated with depressive and anxiety disorders.12 There is a need to collectively analyze psychiatric comorbidities in light of suicide ideation and migraine as previous studies have demonstrated that patients with migraine have a higher risk of developing suicidal behavior.13 Utilizing the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, a cross-sectional study focused on the relationship between suicidal behavior and several psychiatric disorders such as non-psychotic depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).13 Hospitalized patients with migraine had about a three-fold increased risk of suicidal behaviors; this risk was lower in patients under 50 years old.13 Individuals in the depression/migraine subgroup had a reduced risk of suicidal behavior in comparison to the migraine population without depression, in which the risk of suicidal ideation was greater than two-fold.13 Individuals in the anxiety/migraine subgroup also demonstrated a reduced risk of suicidal behaviors while an association between PTSD, migraine, and suicidal ideation was not found at all.13 These results highlight the need to assess migraine and psychiatric comorbidities collectively as opposed to juxtaposing migraine with individual disorders.

Sleep-wake disorders

Similar to depression, the relationship between sleep and migraine is thought to be bidirectional in that each can potentially affect the outcome of the other.14 The connection between sleep and migraine might extend to a common pathophysiology as supported by recent evidence.14 In addition to shared mediating signaling molecules, it is thought that subcortical structures common to both sleep and migraine contribute to their link.14

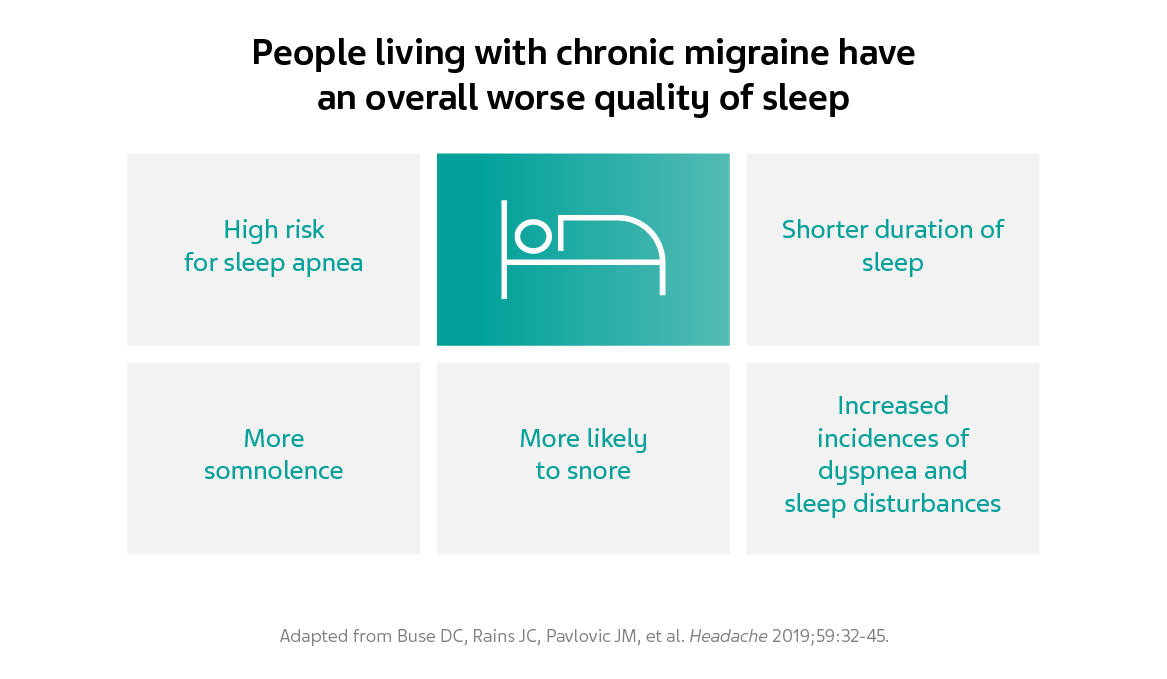

A close relationship between sleep and migraine may be evident as 36% of people living with migraine reported insomnia and 16% reported sleep apnea as comorbidities in the ARMR study.2 Comparatively, the CaMEO study employed objective measures to study sleep quality; of the almost 13,000 participants with migraine, 37% were at high risk for sleep apnea according to the Berlin questionnaire, which is comprised of three categories related to the risk of sleep apnea.15 Furthermore, the CaMEO study delved into the differences in sleep quality between people living with CM and EM.15 Those with CM were at a higher risk for sleep apnea, were more likely to snore, experienced episodes of dyspnea and sleep disturbances, and overall had a worse quality and duration of sleep than those with EM (Figure 4).15 Additionally, results from the MAST study demonstrated that those with poor sleep had a statistically higher rate of anxiety and depression as well as a greater intensity and lengthier duration of migraine.3 This reinforces the need to look at migraine and psychiatric comorbidities on a holistic level.

Figure 4. People living with chronic migraine have an overall worse quality of sleep.

The tip of the iceberg

Depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and sleep disorders are only some of the psychiatric conditions that are associated with migraine. Throughout the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, migraine is listed as a comorbidity for various psychiatric disorders including bipolar disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, restless leg syndrome, etc.12 Although each condition is an individual disorder, studies indicate an interplay between migraine and several psychiatric comorbidities.3,13 In order to better serve people living with migraine, it is vital to acknowledge this interplay in the context of advancing our understanding of migraine and associated comorbidities.

References

- Dresler T, Caratozzolo S, Guldolf K, et al. Understanding the nature of psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a systematic review focused on interactions and treatment implications. J Headache Pain 2019;20:51.

- Schwedt TJ, Digre K, Tepper SJ, et al. The American Registry for Migraine Research: Research Methods and Baseline Data for an Initial Patient Cohort. Headache 2020;60:337-47.

- Buse DC, Reed ML, Fanning KM, et al. Comorbid and co-occurring conditions in migraine and associated risk of increasing headache pain intensity and headache frequency: results of the migraine in America symptoms and treatment (MAST) study. J Headache Pain 2020;21:23.

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1789-858.

- Antonaci F, Nappi G, Galli F, Manzoni GC, Calabresi P, Costa A. Migraine and psychiatric comorbidity: a review of clinical findings. J Headache Pain 2011;12:115-25.

- Yang Y, Zhao H, Heath AC, Madden PA, Martin NG, Nyholt DR. Shared Genetic Factors Underlie Migraine and Depression. Twin Res Hum Genet 2016;19:341-50.

- Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:428-32.

- Buse DC, Greisman JD, Baigi K, Lipton RB. Migraine Progression: A Systematic Review. Headache 2019;59:306-38.

- Ashina S, Serrano D, Lipton RB, et al. Depression and risk of transformation of episodic to chronic migraine. J Headache Pain 2012;13:615-24.

- Farris SG, Burr EK, Abrantes AM, et al. Anxiety Sensitivity as a Risk Indicator for Anxiety, Depression, and Headache Severity in Women With Migraine. Headache 2019;59:1212-20.

- Klenofsky B, Pace A, Natbony LR, Sheikh HU. Episodic Migraine Comorbidities: Avoiding Pitfalls and Taking Therapeutic Opportunities. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2019;23:1.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2013:xliv, 947-xliv,

- Friedman LE, Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Williams MA, Peterlin BL. Association Between Migraine and Suicidal Behaviors: A Nationwide Study in the USA. Headache 2018;58:371-80.

- Vgontzas A, Pavlović JM. Sleep Disorders and Migraine: Review of Literature and Potential Pathophysiology Mechanisms. Headache 2018;58:1030-9.

- Buse DC, Rains JC, Pavlovic JM, et al. Sleep Disorders Among People With Migraine: Results From the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache 2019;59:32-45.

NPS-US-NP-01578