The history of migraine, evolution of treatment, and current social disparities

The type of headache now widely recognized as migraine has been reported since the ancient Greek period and has affected people throughout history—however, it was long deprived of the attention it deserved because headache as a symptom has often been minimized and dismissed.1 Management options have greatly improved as migraine was acknowledged in the last decade as one of the three most prevalent medical conditions in the world.2 However, many issues still remain to be addressed in creating health equity for the vast number of people living with migraine.3

The history of migraine diagnosis and the role of gender

Because of the higher prevalence of migraine in women compared to men,4 migraine was ignored by many during the 19th century as a disease affecting “overworked maids or female factory-hands.”5 People with migraine were denied acknowledgement of their symptoms by medical professionals, and left without treatment options.5 A shift occurred in 1870 when English physician Hubert Airy reported a new condition—then coined “transient teichopsia” characterized by visual auras and “oppressive” headache—and proposed that it could occur as a “consequence of intellectual fatigue in well-educated men.”5

Nervous and vascular involvement quickly began to be explored as the mysterious headache finally started to garner interest in the medical and scientific community.5 Though research progressed in the following years, it was not until 1962 that a formal modern definition of migraine was published for the first time by the Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache.6 What we recognize as migraine today was characterized in this document as “recurrent attacks of headache, widely varied in intensity, frequency and duration. The attacks are commonly unilateral in onset, are usually associated with anorexia and sometimes with nausea and vomiting; some are preceded by, or associated with, conspicuous sensory, motor, and mood disturbances; and often familial.”6

Thereafter, the definition and diagnostic criteria of migraine continued to evolve, and still remains fluid today.7 The third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) includes the most current diagnostic criteria for episodic migraine (with and without aura) and chronic migraine used worldwide today, and these are likely to keep changing as research on migraine continues to progress.8

Is migraine vascular or neurological in nature? The evolution of treatment

Whether the pathophysiology of migraine is vascular or neurological in nature has been debated for over 100 years, and the detailed history has been reviewed extensively.9

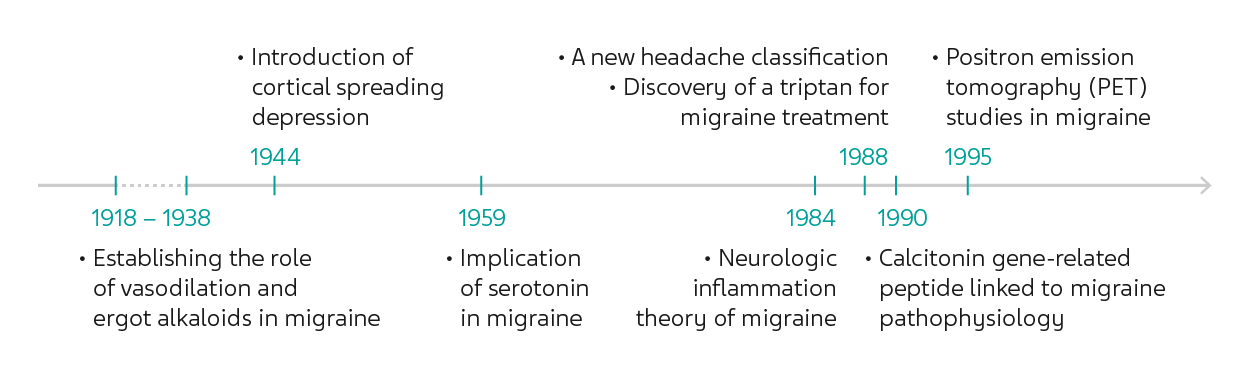

While both avenues were proposed and explored shortly after “transient teichopsia” was first described,5 early 20th century studies on vascular involvement in migraine10 contributed to the 1946 approval of ergotamine derivatives (which have vasoconstrictor activity) for migraine treatment in the US.5 In the quickly moving world of research, however, studies supporting the theory of migraine as a chronic neurological disorder started gaining more attention during this time.5 One of the key events in this era was the first description of cortical spreading depression,11 later revealed to have an important relationship with migraine.9

In the 1950s, serotonin was isolated and implicated in migraine biology, along with the introduction of a serotonin inhibitor as a preventive treatment.12 In the following decades, studies mainly supporting neurological processes underlying migraine pathophysiology continued to populate the literature.9 More options for treatments became available both in terms of medications, including antiemetics and anticonvulsants, and in terms of care, with the emergence of specialist migraine clinics.5 In 1984, neurologic inflammation was implicated in migraine, suggesting an important link between the trigeminovascular system and migraine pathobiology.13

A triptan showing efficacy in treating migraine was discovered in 1988,14 leading to its EU and US approval in 1991 and subsequent wide adoption as a first-line treatment.5 It was also in 1988 that migraine was clearly classified by the Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society, ensuring that scientific research could be standardized in comparable patient populations across the world.9

In 1990, the role of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in migraine pathophysiology was documented, opening more avenues for further research and treatment options that are specific to migraine.15 During the most recent decades, technical advancements have led to further expansion of brain imaging including using positron emission tomography (PET) to examine migraine, as well as high throughput examination of genetic data relevant in migraine, and these have contributed to increasingly sophisticated knowledge of the intricacies of migraine pathophysiology.9 Nevertheless, even today, the vascular and neurological theories of migraine are still debated,9 and the collective understanding is still in evolution.7

Current state of social disparities in migraine care and treatment

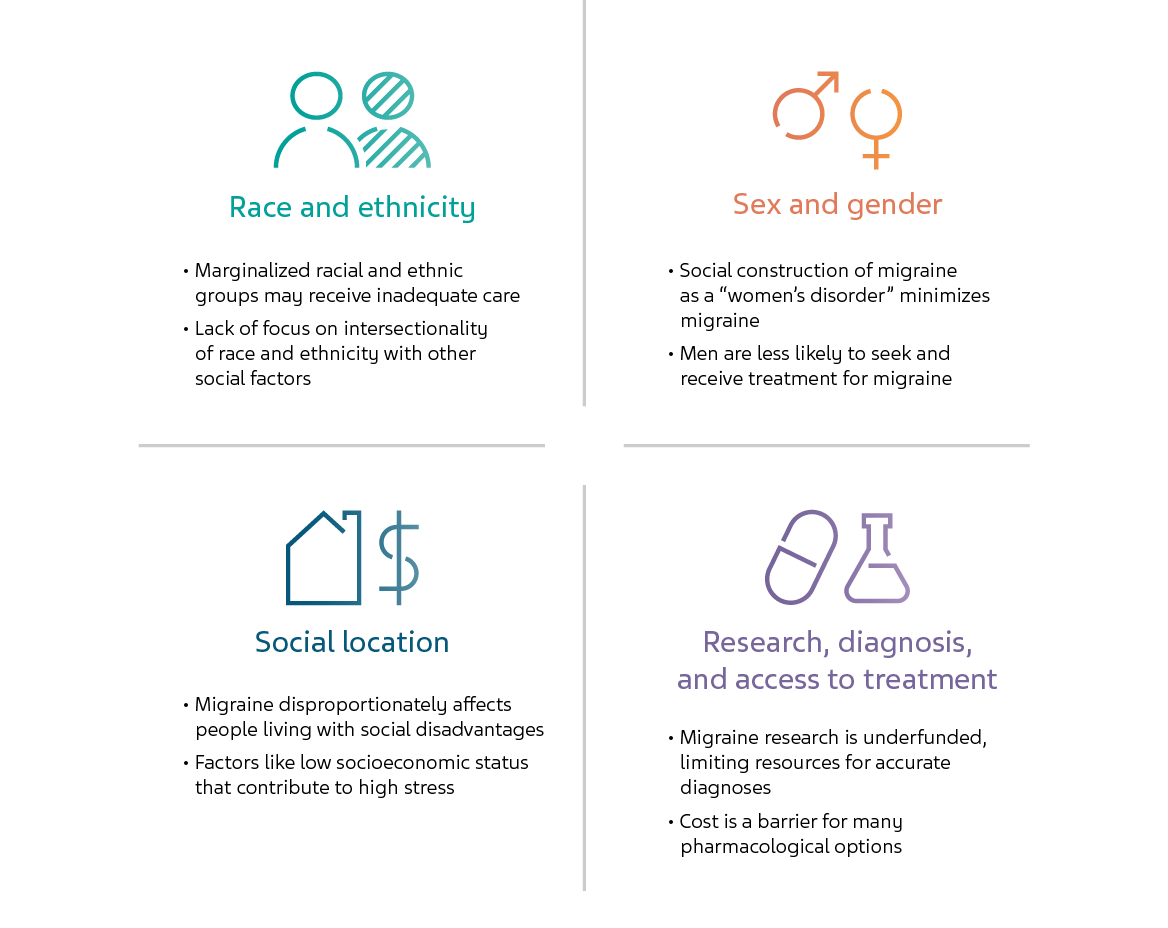

Though our knowledge about migraine, as well as management and treatment options for people living with migraine, have improved greatly over history, social disparities in diagnosis and treatment remain a major issue today as lower income countries face problems of access and costs.3 Even within developed nations, disparities based on racial, ethnic, gender, and socioeconomic differences require attention, as marginalized groups have been reported to bear a disproportionate burden of migraine.3

RACE AND ETHNICITY

A study from the US reported the average prevalence of severe headache or migraine from 2005 to 2012 was 17.7% for Native Americans, 15.5% for White Americans, 14.5% for Hispanic Americans, 14.45% for African Americans, and 9.2% for Asian Americans.16 Importantly, it was found that Hispanic Americans make only 89.5 annual ambulatory care visits per 10,000 population during which they receive a diagnosis of migraine, compared with 176.3 for White Americans and 133.2 for African Americans.16 These data are consistent with the established notion that people of color tend to be less likely to seek medical care and receive a diagnosis and treatment for migraine.3

SEX AND GENDER

Migraine affects women more than men, peaking at approximately 3.25 times greater prevalence in women compared with men in the age group of 18 to 29 years.4 The social construction of migraine as a “women’s disorder” has been deeply rooted, creating difficulties for all gender identities.3 In addition to pain reported by women being susceptible to being ignored or minimized, the social stigma also contributes to men being less likely to seek diagnosis or treatment for migraine.3

SOCIAL LOCATION

Migraine disproportionately affects people in difficult “social locations” which may include factors including low annual household income, food insecurity, lack of personal safety, lack of access to healthcare, and unemployment, causing a high amount of stress.3 Research has demonstrated that a household income greater than $90,000/year reduces the rate of migraine by almost half, people with health insurance are nearly twice as likely to receive a migraine diagnosis, and household income is directly related to using appropriate therapies, illustrating the effects of social location.17

RESEARCH, DIAGNOSIS, AND ACCESS TO TREATMENT

Though migraine is one of the most widespread and disabling of all neurobiological disorders, migraine research is among the lowest funded areas of research; this contributes to limited resources being available for patients to receive, and their clinicians to achieve, optimal diagnoses.3 Furthermore, the many pharmacological treatments now available are still out of reach for many people living with migraine, as 57% of uninsured patients have been reported to not seek care because of cost.17

Migraine care has improved, but not for everyone

Though extraordinary advances have been made in migraine diagnosis, care, and treatment, current literature shows that the incidence and severity of migraine are influenced by many social factors that disproportionately affect marginalized groups.3 The migraine experience is complex and deeply personal, and varies greatly among individuals living with migraine—the medical community should continue to address these issues to strive to provide health equity for all.3

References

- Rose FC. The history of the migraine trust. J Headache Pain 2006;7(2):109–15.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Birbeck GL. Migraine: the seventh disabler. J Headache Pain 2013;14(1):1.

- Befus DR, Irby MB, Coeytaux RR, Penzien DB. A Critical Exploration of Migraine as a Health Disparity: the Imperative of an Equity-Oriented, Intersectional Approach. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2018;22(12):79.

- Buse DC, Loder EW, Gorman JA, et al. Sex Differences in the Prevalence, Symptoms, and Associated Features of Migraine, Probable Migraine and Other Severe Headache: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 2013;53(8):1278–99.

- Barnett R. Migraine. The Lancet 2019;394(10212):1897.

- Ad Hoc Committee on Classification of Headache. Classification of headache. JAMA 1962;179(9):717–8.

- Medrea I, Christi S. Chronic Migraine - Evolution of the Concept and Clinical Implications. Headache 2018;58(9):1495–500.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38(1):1–211.

- Tfelt-Hansen PC, Koehler PJ. One hundred years of migraine research: major clinical and scientific observations from 1910 to 2010. Headache 2011;51(5):752–78.

- Graham JR, Wolff HG. MECHANISM OF MIGRAINE HEADACHE AND ACTION OF ERGOTAMINE TARTRATE. Arch NeurPsych 1938;39(4):737–63.

- Leao AAP. Spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology 1944;7(6):359–90.

- Sicuteri F. Prophylactic and therapeutic properties of 1-methyl-lysergic acid butanolamide in migraine. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol 1959;15:300–7.

- Moskowitz MA. The neurobiology of vascular head pain. Ann Neurol 1984;16(2):157–68.

- Humphrey PP, Feniuk W, Perren MJ, et al. GR43175, a selective agonist for the 5-HT1-like receptor in dog isolated saphenous vein. Br J Pharmacol 1988;94(4):1123–32.

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R. Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann Neurol 1990;28(2):183–7.

- Loder S, Sheikh HU, Loder E. The prevalence, burden, and treatment of severe, frequent, and migraine headaches in US minority populations: statistics from National Survey studies. Headache 2015;55(2):214–28.

- Charleston L, Royce J, Monteith TS, et al. Migraine Care Challenges and Strategies in US Uninsured and Underinsured Adults: A Narrative Review, Part 1. Headache 2018;58(4):506–11.

NPS-US-NP-01548