The female migraine: Sex-specific presentation of migraine

Migraine is significantly more prevalent in women than in men, affecting 17.0% of women and 8.6% of men globally.1,2 Migraine symptoms appear to shift with fluctuating female sex hormone levels during a woman’s life course.1 Studies are starting to unravel possible mechanisms by which migraine may impact women at their various life stages in unique ways.3

Sex differences in migraine prevalence

Approximately three to four times more women are affected by migraine compared with men throughout the lifespan, with differences emerging after puberty.4,5 From adolescence onward, women exhibit a higher level of headache-related disability and longer recovery periods compared with men.4,5 Women may also have a higher risk of transitioning to chronic migraine.6 Furthermore, chronic migraine has been associated with menstrual-cycle disorders including dysmenorrhea, and migraine headaches are also more frequent in women with endometriosis and fertility issues.5

Neuroimaging studies have confirmed structural and functional differences between men and women with migraine.5 Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that the posterior insular cortex and precuneus are thicker in women compared to men with migraine.5,7 Human studies have shown increased sex-specific activity in particular areas of the brain involved in pain processing (insula and precuneus), but the basis of these sex differences is still not well understood.6 While a number of, and an interplay between, both genetic and non-genetic factors contribute to sex differences in migraine pathogenesis, the current body of evidence suggests that the role of sex-specific hormones plays a major part.1

Impact of hormones on women with migraine

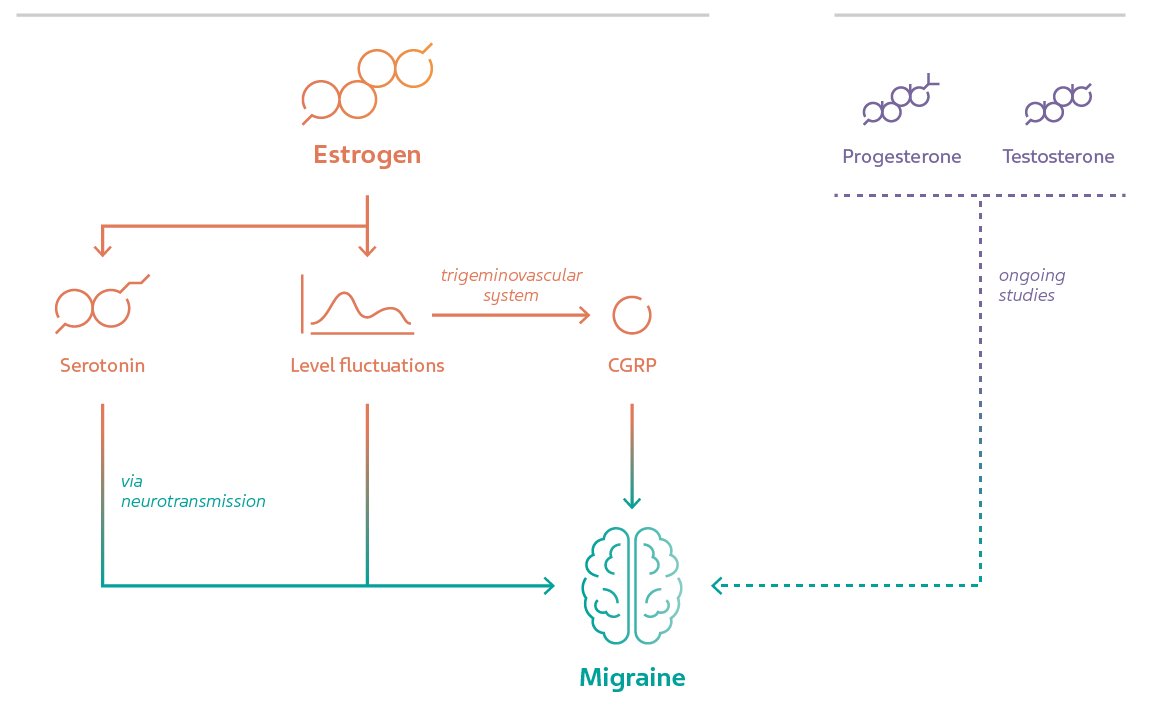

Growing evidence suggests estrogen is a major player in migraine.1 Female gonadal hormones increase migraine susceptibility in animal models, which is abrogated by ovariectomy.8 Women who are obese appear to have a greater than two-fold risk of migraine compared to non-obese women, which is hypothesized to be related to pathological estrogen production in adipose tissue.9 A recent systematic review showed that high estrogen levels, estrogen fluctuations, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) were associated with the worst migraine outcomes.7 Ongoing studies continue today to elucidate mechanisms involved in the relationship between estrogen and migraine.1

Fluctuations in estrogen have a strong influence on a number of neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, catecholamines, and endorphins.7 One possible link between estrogen and migraine pathogenesis lies in the serotonergic system.9 Estrogen enhances serotonin neurotransmission, which plays a crucial role in migraine pathogenesis.10 Another emerging link is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) release, a major contributor to migraine pathology, which also appears to be modulated by fluctuating estrogen levels.11,12 Several studies have indicated a connection between estrogen (and other female sex hormones) and CGRP expression, along with homeostasis of the trigeminovascular system, which remains an active area of research.3,12

In contrast to estrogen, testosterone can suppress migraine in animal models via androgen receptor signaling,13 though its effect in humans is not yet clear due to a lack of relevant studies. Likewise, the role of progesterone and other sex specific hormones have been less thoroughly studied, though some existing data suggest a connection with migraine.9 Allopregnanolone (a derivative of progesterone and pregnenolone) is the centrally acting progesterone in the central nervous system which enhances gamma-aminobutyric acid function, thereby inhibiting neuronal excitability.14 Progesterone is thought to have a neuroprotective effect by reducing nociception in the trigeminovascular system, which may reduce neurogenic inflammation in migraine.14 Though further investigation is necessary, it is evident that hormones are a critical part of understanding sex differences in migraine.

Migraine in specific life stages of women

MIGRAINE IN MENARCHE AND ADOLESCENCE

Sex differences in migraine prevalence emerge at the start of puberty and increase over the course of adolescence.1 The incidence of migraine with aura is greatest around 12–13 years of age, whereas that of migraine without aura is a few years later, which may be related to unique ovulation patterns and related hormonal changes associated with menarche.9 Despite this, treatment of adolescent migraine remains a challenge due to limited data.1 Medication can be used both symptomatically and preventively, but clinicians must be cautious of certain classes of drugs that may be teratogenic.1

MENSTRUAL MIGRAINE

Menstrual migraine (MM), which encompasses both pure MM and menstrually-related migraine (MRM), is more severe, longer lasting, less responsive to medication, and more likely to be associated with disability than non-menstrually related migraine (NMRM).12,15 MM attacks occur up to 2 days prior to, during, and/or up to 3 days after menstruation in at least 2 out of 3 cycles.12,16 Typically, MM presents without aura, and while only 10–20% of women experience pure MM, 60% of women experience MRM.1,12

Abrupt decreases in plasma estrogen levels in the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle are thought to trigger MM attacks, known as the ‘estrogen withdrawal hypothesis’.11,12 Women with migraine also have a faster decline of estrogen in the luteal phase than those without migraine.12 Because MM is not responsive to classic medication, temporally targeted preventive hormonal therapy, such as estrogen implants, is more effective.17 Interestingly, genomic studies have revealed that MRM is defined by unique gene expression patterns distinct from NMRM, which may help identify biomarkers in the future.18

HORMONAL TREATMENT AND RISK OF STROKE

Hormonal manipulation can help women with an irregular menstrual cycle by providing a stable hormonal milieu.12 Hormonal contraceptives are heterogenous in hormone ingredients, types, amount, mode of delivery, and dosage; administration can improve, worsen, or have no impact on migraine.1 Generally, most hormonal contraceptives have been accepted as no-risk products for people living with migraine without aura or with simple aura.1

Patients who have migraine with aura, however, are cautioned against using hormonal contraceptives because the risk of ischemic stroke has been suggested by several studies.1 One study demonstrated a two-fold higher stroke risk among women with migraine with aura.12 The risk of stroke is increased with the use of the combined oral contraceptive pill; however, progestogen-only contraceptives have not been shown to increase the risk of stroke.12 The evidence remains controversial, and detailed analyses are ongoing to clarify the significance of the risk, so that informed recommendations can be made.1

MIGRAINE IN PREGNANCY, POSTPARTUM, AND LACTATION

Migraine usually affects women during childbearing years, and an important consideration for clinicians is choosing medications with the least possible teratogenic risk, if symptoms warrant the use of medications.1 Migraine symptoms may worsen in the first trimester due to lifestyle changes, including missed meals due to morning sickness.12 However, studies have shown that symptoms improve for women living with migraine without aura in the second and third trimesters as plasma estrogen levels increase.12,19 Conversely, women living with migraine with aura may have no improvement as the pregnancy progresses, and their symptoms may even worsen.12 Importantly, in pregnancy and the postpartum period, precise distinctions must be made between migraine and various pregnancy-related secondary headache disorders.1 Generally, non-pharmacological therapies are recommended if symptoms are not severe.19

With the rapid drop of estrogen levels after delivery, women often experience a return of migraine symptoms during the postpartum and lactation period; this is compounded by lifestyle changes such as sleep deprivation, irregular meals, and stress.1,12 Special considerations are required for the use of migraine medications during breastfeeding.19 Acute or preventive treatment, if needed, should be carefully selected by considering the benefits and risks for both mother and infant.19

MIGRAINE IN PERIMENOPAUSE AND MENOPAUSE

Symptoms of MM tend to improve with age as women approach menopause, but the interplay of migraine with perimenopausal symptoms can be complicated, leading to worsening of symptoms for a subset of women with migraine.11 The perimenopausal period is associated with an increase in migraine due to fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone.12 Whether HRT has a beneficial effect on migraine is still unclear due to inconsistent data, and warrants further investigation.1 Post-menopause, many women experience alleviation of their migraine symptoms, as hormone levels (namely estrogen) drop and stabilize.1

Further research on migraine in women is crucial

The constantly fluctuating nature of female sex hormones is closely linked to migraine, yet unfortunately remains a relatively under-studied area. Women experience migraine throughout their lives in a different way to men, and future studies should urgently focus more on how both women and men with migraine can benefit from expanded knowledge about sex-specific management recommendations.

References

- Lagman-Bartolome AM, Lay C. Migraine in Women. Neurol Clin 2019;37(4):835–45.

- Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Linde M, Steiner TJ. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain 2022;23:34.

- Labastida-Ramírez A, Rubio-Beltrán E, Villalón CM, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Gender aspects of CGRP in migraine. Cephalalgia 2019;39(3):435–44.

- Buse DC, Loder EW, Gorman JA, et al. Sex Differences in the Prevalence, Symptoms, and Associated Features of Migraine, Probable Migraine and Other Severe Headache: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 2013;53(8):1278–99.

- Al-Hassany L, Haas J, Piccininni M, et al. Giving researchers a headache – sex and gender differences in migraine. Front Neurol 2020;11:549038.

- Schroeder RA, Brandes J, Buse DC, et al. Sex and Gender Differences in Migraine-Evaluating Knowledge Gaps. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27(8):965–73.

- Amiri P, Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, et al. Migraine: a review on its history, global epidemiology, risk factors, and comorbidities. Front Neurol 2022;12:800605.

- Eikermann-Haerter K, Dileköz E, Kudo C, et al. Genetic and hormonal factors modulate spreading depression and transient hemiparesis in mouse models of familial hemiplegic migraine type 1. J Clin Invest 2009;119(1):99–109.

- Delaruelle Z, Ivanova TA, Khan S, et al. Male and female sex hormones in primary headaches. J Headache Pain 2018;19(1):117.

- Martin VT, Behbehani M. Ovarian hormones and migraine headache: understanding mechanisms and pathogenesis--part I. Headache 2006;46(1):3–23.

- Pavlovic JM, Akcali D, Bolay H, Bernstein C, Maleki N. Sex-related influences in migraine. Journal of Neuroscience Research 2017;95(1–2):587–93.

- Afridi SK. Migraine: navigating the hormonal minefield. Pract Neurol 2019;0:1–8.

- Eikermann-Haerter K, Baum MJ, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AMJM, Moskowitz MA, Ayata C. Androgenic suppression of spreading depression in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutant mice. Ann Neurol 2009;66(4):564–8.

- Ahmad SR, Rosendale N. Sex and gender considerations in episodic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2022;26:505–516.

- Pinkerman B, Holroyd K. Menstrual and nonmenstrual migraines differ in women with menstrually-related migraine. Cephalalgia 2010;30(10):1187–94.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38(1):1–211.

- Magos AL, Zilkha KJ, Studd JW. Treatment of menstrual migraine by oestradiol implants. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1983;46(11):1044–6.

- Hershey A, Horn P, Kabbouche M, O’Brien H, Powers S. Genomic Expression Patterns in Menstrual-Related Migraine in Adolescents. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 2012;52(1):68–79.

- Robbins MS. Headache in Pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2018;24(4, Headache):1092–107.

NPS-US-NP-01585