Medication overuse headache in migraine: A vicious cycle

Medication overuse headache (MOH) is a chronic secondary headache disorder.1 According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, MOH is defined as headache occurring on 15 or more days per month developing as a consequence of regular overuse of acute or symptomatic headache medication.2 More specifically, it is attributed to the overuse of analgesics or acute medication to treat a primary headache disorder.1,2

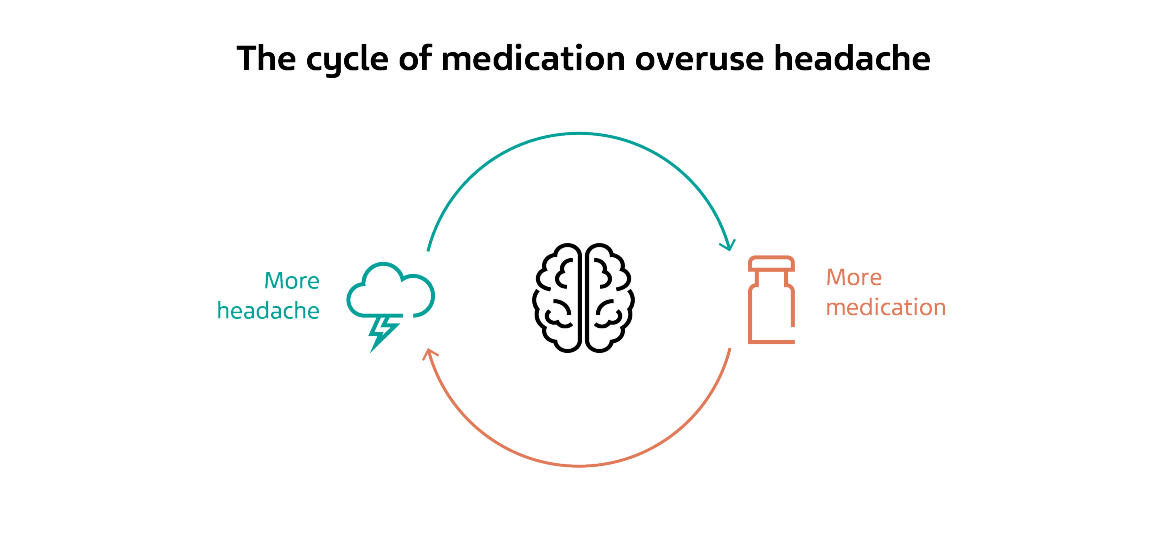

Migraine and MOH are inevitably intertwined; previous primary headache, such as but not limited to migraine, is required for development of MOH, a secondary headache disorder that is debilitating in its own right.3 The relationship between migraine and MOH manifests in a vicious cycle, which begins when individuals with migraine fall into medication overuse in the efforts to symptomatically treat their headache attacks.1 This, in turn, causes the more severe and/or more frequent headache associated with MOH, which leads the patient to use even more medication to treat the worsening symptoms.1

The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) system, which has been heavily implicated in the pathophysiology of migraine, may play a role in MOH as well.4 Blocking CGRP or its receptors has been shown to prevent MOH formation and reduce headache in MOH treatment.4 The use of acute medication for treatment of migraine, as well as the use of analgesics for other indications such as lower back pain, can increase the frequency and intensity of headache attacks in individuals with migraine.1

Overuse of acute treatments

The overuse of several classes of drugs used for the acute or symptomatic treatment of migraine, including analgesics, opioids, triptans, and ergots, can lead to MOH onset.5 Depending on the type of medication, overuse is defined as the use of the medication on 10 days per month (triptans, ergots, opioids) or 15 days per month (non-steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen).2,6 Though medication overuse contributes to headache chronification, greater pain intensity, and increased disability, not all patients who frequently use acute medications to abort headache attacks will develop MOH.6

The rate of MOH associated with analgesics and opioids is considerably higher than the rate of MOH associated with triptans and ergots.7 Migraine, when accompanied by pain as well as disability and burden, often necessitates the use of the acute treatments mentioned above.6 The disability caused by migraine is quantifiably significant; migraine was the second‑leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide in 2016.8 As such, the use of analgesics in people with migraine is considered justified when utilized correctly.6

For decades, clinicians have reported the chronification of primary headache disorders during periods of frequent use of analgesics.6 Long-term overuse of even simple analgesics can result in serious side effects and lasting harmful effects on headache.7 Barbiturate‑containing analgesics were associated with a more than 70% overall increased risk of chronic migraine onset.5 Opioids are associated with a 44% increase in the risk of migraine onset.5 Triptans are not a risk factor for chronic migraine onset overall, but in patients with a higher frequency of episodic migraine (10 to 14 days per month), the risk of chronification increases with the frequency of triptan use.5

MOH in migraine: Difficulties of diagnosis

MOH is a complex disorder that is difficult to classify and diagnose.9 The adverse effect of medication overuse is commonly unacknowledged, both by healthcare providers and individuals who experience headache.9 In the past, shortcomings in the diagnosis of MOH have led to confusion and a lack of clarity regarding the extent of the problem.9 With these issues, identifying and treating individuals with MOH becomes more difficult, so proper diagnosis of the condition is vital.9

The prevalence of MOH has been estimated to be between 0.5% and 7.2% globally.9 This wide range is, in large part, due to a lack of universal standards for classifying and diagnosing MOH globally.9 A common case definition of MOH would allow population-based prevalence studies to gain more accurate estimates of the scope of the disease.9

Another contributing factor to the difficulties of MOH diagnosis is the connection between MOH and migraine. The clinical features of MOH are often similar to those of the underlying primary headache disorder.10 In individuals with migraine, headaches from overuse can be migraine-like in nature, though people have often stated that they can distinguish between their migraine headache and overuse headache.10 Still, the similarity between the clinical features of the two conditions contributes to the complexity of proper diagnosis of MOH.10

Treatment strategies for MOH and migraine

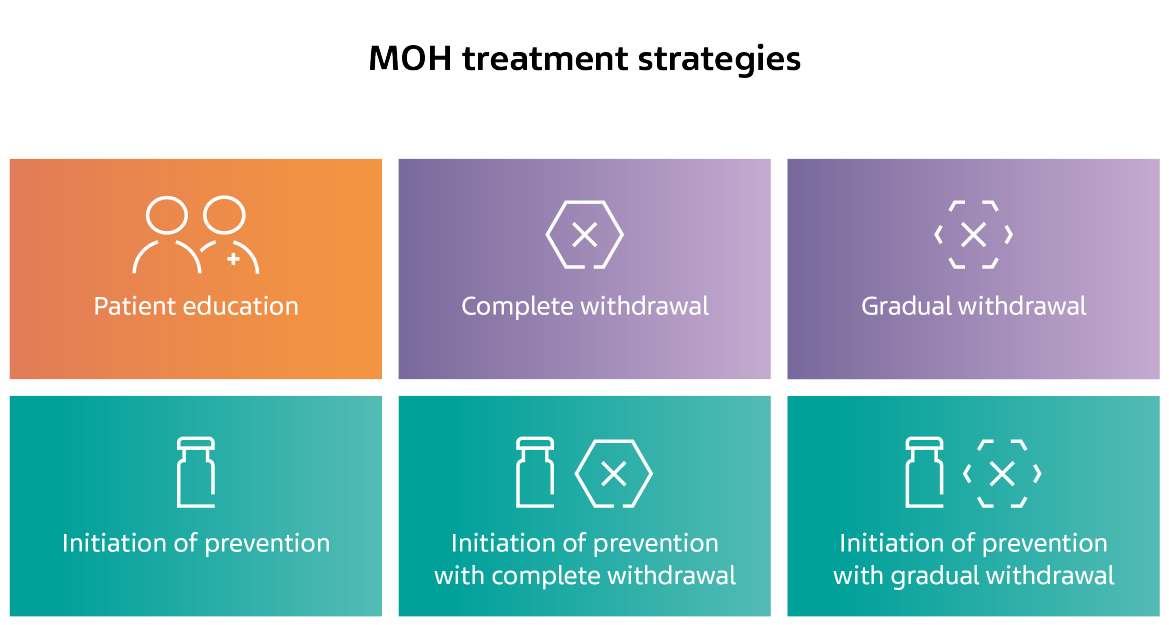

While there is substantial information available on MOH treatment strategies, there is no consensus among experts on the best strategy to treat the disease. In general, treatment usually involves nonpharmacological intervention, modifications of acute treatment, preventive treatment, or some combination of the three.5

A recent clinical trial compared three strategies; complete withdrawal from acute medication, the use of preventive treatment, and withdrawal plus preventive treatment.11 The study found that all three strategies were effective in treating MOH, but the withdrawal plus preventive group had the numerically largest reductions in headache days, migraine days, and headache pain intensity.11 Withdrawal plus preventive treatment was also the most effective strategy in curing MOH and reverting from chronic headache to episodic headache.11

For migraine, the path to effective treatment has been met with several challenges, including the risk of developing MOH.4 Better acute treatment that is less likely to lead to overuse could fill this need. Two classes of drugs have been identified that could improve the acute treatment of migraine: 5-HT receptor antagonists and small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists.4

Additionally, preventive treatments could provide the answer for the more effective treatment of migraine.5 Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAb) have emerged as a viable option for the preventive treatment of migraine. Some of these mAbs have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the number of headache days in patients with migraine and reduce daily analgesic intake, which could be useful in lowering the prevalence of MOH.12 Preventive treatment is useful for the direct treatment of MOH, especially when combined with withdrawal from acute medication.11

For migraine, the path to effective treatment has been met with several challenges, including the risk of developing MOH.4 Better acute treatment that is less likely to lead to overuse could fill this need. Two classes of drugs have been identified that could improve the acute treatment of migraine: 5-HT receptor antagonists and small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists.4

Additionally, preventive treatments could provide the answer for the more effective treatment of migraine.5 Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAb) have emerged as a viable option for the preventive treatment of migraine. Some of these mAbs have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the number of headache days in patients with migraine and reduce daily analgesic intake, which could be useful in lowering the prevalence of MOH.12 Preventive treatment is useful for the direct treatment of MOH, especially when combined with withdrawal from acute medication.11

References

- Diener HC, Dodick DW, Evers S, et al. Pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of medication overuse headache. Lancet 2019;18:891–902.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1-211.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1-211.

- van Hoogstraten WS, MassenVanDenBrink A. The need for new acutely acting antimigraine drugs: moving safely outside acute medication overuse. J Headache Pain 2019;20.

- van Hoogstraten WS, MassenVanDenBrink A. The need for new acutely acting antimigraine drugs: moving safely outside acute medication overuse. J Headache Pain 2019;20.

- van Hoogstraten WS, MassenVanDenBrink A. The need for new acutely acting antimigraine drugs: moving safely outside acute medication overuse. J Headache Pain 2019;20.

- Alstadhaug KB, Ofte HK, Kristoffersen ES. Preventing and treating medication overuse headache. Pain Rep 2017;2.

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211-59.

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211-59.

- Ailani J. Medication-Overuse Headache. Pract Neurol 2020:67–71.

- Carlsen LN, Munksgaard SB, Nelsen M, et al. Comparison of 3 Treatment Strategies for Medication Overuse Headache. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:1069–78.

- Pellesi L, Guerzoni S, Pini LA. Spotlight on Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies in Migraine: The Clinical Evidence to Date. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2017;6:534-47.

NPS-US-NP-01549