Hormones in migraine pathophysiology

Migraine is a neurologic disease that is experienced by roughly 10% of the global population.1 However, men and women do not experience this disease in the same way; migraine is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women compared with men.2 The difference peaks at 3.25 times greater prevalence in women than in men among those aged 18–29.3 Women with migraine also have more frequent and intense headaches, a higher risk of chronification (transition from episodic migraine to chronic migraine), and greater headache-related disability than men with migraine.2

It is no coincidence that there are differences in migraine between the sexes. Migraine prevalence is similar between the sexes before puberty, with incidence increasing during reproductive milestones in women when hormonal fluctuations occur.2 In men, however, the course of migraine throughout their lifespan appears relatively stable.4 This is because female sex hormones have a unique role in migraine pathophysiology and, consequentially, in the phenotype of migraine.4 Because of this, understanding the relationship between hormones and migraine could help to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the disease.

Migraine pathophysiology: Hormones and CGRP

Recognizing how sex hormones affect migraine symptoms begins with understanding its pathophysiology. Migraine is associated with dysfunction of the nociceptive trigeminovascular system.2 The trigeminovascular system conveys nociceptive information from the meninges to the central areas of the brain.1 The characteristic throbbing pain of headache that is associated with migraine is a result of trigeminovascular pathway activation,1 beginning peripherally upon stimulation of nociceptive neurons and release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1

One of these neuropeptides, which has been heavily implicated in the pathophysiology of migraine, is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).1 CGRP is a 37-amino acid neuropeptide that is widely distributed throughout the nervous system and is predominantly expressed in Ad and C-fibers.2 CGRP is likely responsible for generating some of the pain that occurs in migraine.1 Because of this, CGRP has been investigated as a target for preventive treatment of migraine, and monoclonal antibodies antagonizing the CGRP pathway have been developed for this purpose.5

Gender-related differences in the CGRP system are implicated in migraine pathophysiology.2 Several animal and human studies have shown that cyclic fluctuations of ovarian hormones modulate CGRP in the peripheral and central trigeminovascular system.2 Additionally, levels of CGRP are higher in women of reproductive age than in men.4 This could be explained by the fact that CGRP appears to be modulated by fluctuations in estrogen levels.6 Migraine attacks are associated with estrogen withdrawal states, where levels of the hormone are the lowest.6 Conversely, there is a decrease of CGRP release in high-estrogen states and a decrease in migraine prevalence.6

Estrogen’s role in migraine

Estrogen, which likely has a multifactorial role in migraine, including direct cellular and genetic modifications in the central nervous system (CNS), is a female sex hormone of particular interest in migraine research.7 In addition to modulating CGRP, estrogen impacts other systems involved in migraine pathophysiology, such as the serotonergic system and the endogenous opioidergic system.4

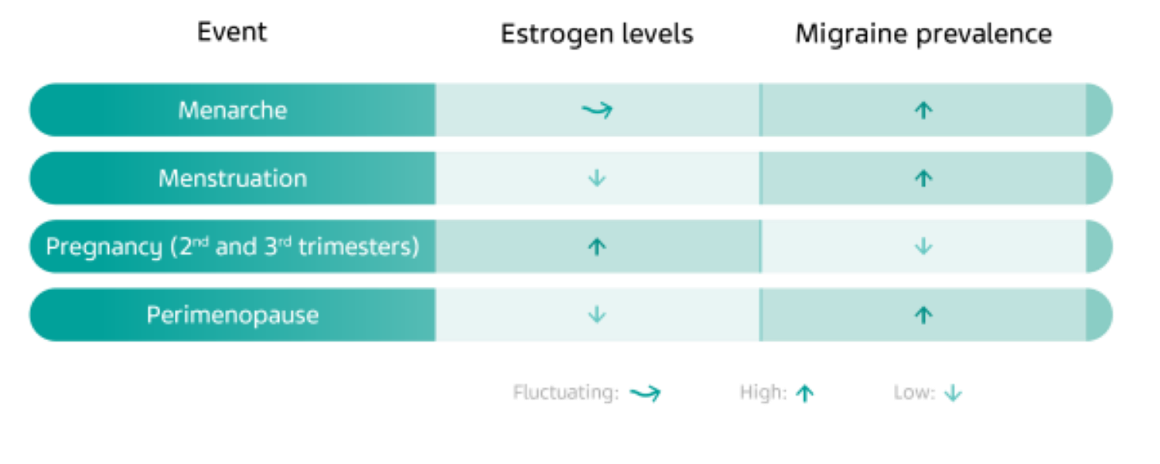

As previously mentioned, due to the hormone’s relationship with CGRP, phases of rising estrogen levels protect against migraine, while lower levels of estrogen are associated with a higher prevalence of migraine.2 As such, migraine can become more or less prevalent throughout a woman’s life depending on when estrogen levels are fluctuating.6

There is an increase in migraine prevalence in women after menarche, the first occurrence of menstruation in a woman’s life.8 Menstrual migraine, characterized by headache that occurs within two days prior to menstrual bleeding, can be attributed to the sudden drop in estrogen during this time.6 High estrogen levels in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy protect against migraine.8 During the transition to menopause, some women may experience an increase in migraine attacks as estrogen levels drop, but this tends to subside in the postmenopausal period of life.8

Hormone therapies and migraine risk

Because of this known relationship between hormones and migraine, medical treatments originally developed to influence female sex hormones in other conditions can also affect migraine prevalence in females, despite initially seeming unrelated to the disease.8

CONTRACEPTIVES

Starting hormonal contraceptives can have varying effects on migraine.8 There are several different forms of contraceptives, but the ones that have been investigated the most thoroughly in relation to migraine are combined oral contraceptives (COCs).8 There is a well‑documented association between COCs and migraine.8 In some cases, however, there is no change in migraine symptoms with COC use.8 In patients with migraine who started COCs, 18–50% reported worsening in frequency or severity of migraine attacks, 3–35% reported migraine improvement, and 39–65% reported no change.8 The use of COCs worsens migraine to a greater extent in migraine with aura than in migraine without aura.8

The use of hormonal contraceptives in migraine patients could also increase cardiovascular risk factors and the use of hormonal contraceptives is associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine.9 In contrast, the use of contraceptives has no effect on the association between migraine and cardiovascular disease outcomes.10

HORMONE REPLACEMENT TREATMENT

Hormone replacement treatment (HRT) is associated with an increased risk of migraine headache.8 HRT is recommended in women with menopause occurring at an early age (before the age of 45) in order to reduce the risks of and relieve the symptoms of menopause.9

However, it is important to note that HRT may trigger migraine attacks in women without a past history of migraine.8 HRT may also cause migraine in women who had migraine before menopause.8 It has further been suggested that HRT could lead to migraine worsening in migraine with aura.11 Higher doses of HRT may also lead to the development of aura symptoms.11 In migraine without aura, HRT has been found to increase migraine attack frequency, days with headache, and analgesic consumption in postmenopausal women.11

HRT is also an important treatment strategy for gender transitions in transgender individuals, a patient population that often encounters discrimination and barriers to treatment.12 It has been suggested that migraine attacks can be exacerbated by gender‑transitioning HRT with estrogen.12,13 More data are needed, however, to better understand the effects of HRT on migraine in transgender individuals.

Significance: Why do we care?

The role of female sex hormones is another piece of the puzzle that is the pathophysiology of migraine. The relationship between estrogen and the CGRP pathway appears to be a key factor in explaining the increased prevalence of migraine in women.2

A look at available literature reveals that the role of estrogen in migraine and its effect on females living with migraine has been well studied.4 Future research on the impact of other sex hormones such as progesterone and testosterone could help further our understanding of migraine and its underlying mechanisms.7 Additionally, the role of COCs and HRT in migraine could be better understood with more investigation.7

Therapies targeting CGRP and its receptor are ushering in a new era of migraine prevention.5 Now that some of these therapies are approved and recommended by headache guidelines, our knowledge of estrogen’s role in modulating CGRP is increasingly important to understanding migraine pathophysiology.2,14 More in-depth knowledge on the sex-related differences in migraine could possibly even contribute to the development of gender‑specific therapies, which could help relieve the burden that many women carry due to migraine.2

References

- Dodick DW. A Phase-by-Phase Review of Migraine Pathophysiology. Headache 2018;58:4–16.

- Labastida-Ramirez A, Rubio-Beltran E, Villalón CM, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Gender aspects of CGRP in migraine. Cephalalgia 2019;39:435–44.

- Buse DC, Loder EW, Gorman JA, et al. Sex Differences in the Prevalence, Symptoms, and Associated Features of Migraine, Probable Migraine and Other Severe Headache: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache 2013;53:1278–99.

- Delaruelle Z, Ivanova TA, Khan S, et al. Male and female sex hormones in primary headaches. J Headache Pain 2018;19:1–12.

- Tso AR, Goadsby PJ. Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies: the Next Era of Migraine Prevention? Headache 2017;19:27.

- Pavlovic JM, Akcali D, Bolay H, Bernstein C, Maleki N. Sex-Related Influences in Migraine. J Neurosci Res 2017;95:587–93.

- Chai NC, Peterlin BL, Calhoun AH. Migraine and estrogen. Curr Opin Neurol 2014;27:315–24.

- Sacco S, Ricci S, Degan D, Carolei A. Migraine in women: the role of hormones and their impact on vascular diseases. J Headache Pain 2012;13:177–89.

- Sacco S, Merki-Feld GS, Ægidius KL, et al. Hormonal contraceptives and risk of ischemic stroke in women with migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Society of Contraception and Reproductive Health (ESC). J Headache Pain 2017;18.

- Kurth T, Winter AC, Eliassen AH, et al. Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2016;353.

- Ripa P, Ornello R, Degan D, et al. Migraine in menopausal women: a systematic review. Int J Women's Health 2015;773-782.

- Irving A, Lehault WB. Clinical pearls of gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender patients. Ment Health Clin 2017;7:164–7.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Dalemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:3132–54.

- Pellesi L, Do TP, Ashina H, Ashina M, Burstein R. Dual Therapy With Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies and Botulinum Toxin for Migraine Prevention: Is There a Rationale? Headache 2020;6:1056–65.

NPS-US-NP-01550